Photo by Nathan Pask

I can remember exactly when I “discovered” Bompas and Parr. It was April 2009 and they were doing an event—part culinary jape, part performance art, part science fair experiment—that went by the name of “Alcoholic Architecture.” They took over a space in London’s Soho, and as visitors arrived they were decked out in protective suits, then ushered into an area filled with an all-enveloping, aromatic cloud. The cloud consisted of vaporized gin and tonic.

A real gin and tonic, in liquid form, is regarded as a perfect delivery system for getting alcohol into the blood stream, with the bubbles in the tonic accelerating the absorption of the gin. But it’s not nearly as efficient as walking into a cloud of the stuff. This way the gin not only enters the body via the mouth, but also the nose, and even, according to Bompas and Parr, through the eyeballs. Half an hour in that room was enough to get most people thoroughly buzzed, and it certainly made those Las Vegas bars where you stand around in an ice vault sipping vodka seem positively tame.

“Alcoholic Architecture” was a lark, but a huge amount of thought and work had gone into it. Vaporizing gin and tonic isn’t something you can just do on a whim. Equally, word was that serious medical opinion had been sought to get the concentrations in the vapor just right so that the end result wasn’t a room full of paralytic drunks, or worse. Sam Bompas and Harry Parr presided benignly over proceedings—a pair of clever, dandyish, enthusiastic, very English young men.

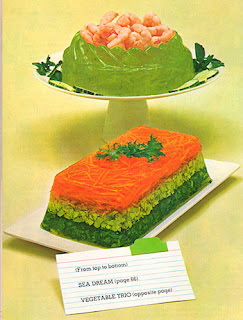

Having “discovered” them, I soon realized they didn’t need any discovering. A small but highly significant part of the world already knew all about them, a world that included celebrity chefs, corporate sponsors, art galleries and English country houses. This world knew them best as “jellymongers” and jelly was their first love as well as their first medium.

Some cultural clarification may be necessary here. Jelly is the British generic term for the America product Jell-O, a linguistic difference largely necessitated by international patent law. The folks who manufacture gelatin desserts in Britain have done just fine without paying to use the methods patented by the inventors of Jell-O. Whereas Jello-O is a powder, British jelly usually comes in concentrated rubbery cubes, though Bompas and Parr actually use leaf gelatin.

The Bompas and Parr story began in 2007 at London’s Borough Market where they tried to set up a stall selling jellies to the public. The management told them to get lost but they succeeded in getting a few commissions to make jellies for private parties. The timing was right. Britain was thoroughly food-obsessed, and jelly fitted in with a nostalgia both for Britain’s heritage (both Henry VIII and Queen Victoria were great jelly enthusiasts, apparently) and also for childhood. However sophisticated the British palate had become, there was still an atavistic longing for food that was sweet, wobbly and fun.

The business took off, but Bompas and Parr were far too smart and quirky to settle for simple nursery school shapes and flavors. Harry Parr was trained as an architect and when it came to making jelly moulds he had access to the computer technology used to create architectural models. Before long he was making jellies in the shapes of buildings designed by cutting edge architects such as Norman Foster and Richard Rogers. It tickled something both in the public’s imagination and in the media.

A terrific, glossy book by Bompas and Parr, published this year, simply titled Jelly, demonstrates the range of possibilities: funeral jellies using black cherry, Prosecco and gold leaf; a Christmas pudding jelly containing Hippocras (a spiced wine punch supposedly devised by Hippocrates); flambé ed jellies arranged into a diorama of the Great Fire of London; and fluorescent jellies that glow in ultraviolet light, a version of which was seen at San Francisco MOMA.

The sensibility that made jelly weird, wonderful and playfully grown-up could also be applied to other aspects of food. Bompas and Parr’s non-jelly projects have included a twelve course Victorian breakfast served at Warwick Castle (a meal that had to be cooked in three separate kitchens), an all black banquet for the London Design Festival, and an occasion on which they flooded an 18th century house in London with over four tons of Courvoisier punch, creating an “architectural punchbowl” big enough to row across: structural engineers had to be called in to ensure that the building didn’t collapse.

Bompas and Parr also organized Britain’s first “flavor tripping party” where they fed their guests with freeze-dried miracle fruit (the legendary West African berries that make bitter and sour foods taste sweet, so that vinegar tastes like sherry, hot sauce tastes like a sugar syrup), then invited them to tuck into a buffet.

There’s always an element of stunt in these events, but they actually do address—in a determinedly unsolemn manner—the whole issue of how we experience food and flavor, how setting and atmosphere affect our perceptions and the extent to which we eat with our eyes and brains.

I recently met up with Sam Bompas and Harry Parr in London, at Whiteleys, an upscale shopping mall (and originally London’s first department store) where they’d set up a temporary “artisanal chewing gum factory” in a couple of empty shops. The artisans were the customers themselves: this was do-it-yourself chewing gum making. Visitors first entered a dramatically lit space, much like an art gallery, where two hundred jars of flavored liquids were on display. You were free to open the jars and sniff the contents to your heart’s content, then had to choose just two to add to your gum. Flavors included fruits, flowers, alcohol, herbs, some far more outré than others. And of course the totally off-the-wall ones really got people excited: white and black truffle, tobacco, bacon, curry. I gamely entered into the spirit of the thing.

The boys were nothing if not encouraging. I chose gin as my first flavor, which was perhaps a little obvious, and then I wondered aloud if they had any ambergris. “Absolutely!” Sam said enthusiastically. This wasn’t quite as unlikely as it might seem: I’d read that they’d used ambergris-flavored cream in one of their earlier projects.

Sam disappeared behind a curtain and in due course returned with a tiny vial containing the essence of gin and ambergris. I then moved on to a second, much more businesslike room, a workshop-cum-kitchen where the chewing gum actually was made. It started with gum base that had been melted in a microwave, and frankly looked like gum that already been chewed, but then I added my flavors, along with powdered sugar and acetic acid, and then some coloring—blue seemed most appropriate—and after much stirring, kneading and rolling, I ended up with six balls of strangely attractive aquamarine gum.

Harry assured me along the way that I was doing a great job, though I felt decidedly ham-fisted. And afterwards Sam suggested that I wait a day or two to let the gum “mature” before eating it, though I couldn’t help wondering if this was so he’d be a long way away should I experience nausea and gagging. But in fact my gum tasted pretty good. I tried it out on a few more or less willing friends and it got some decent reviews. The words “a nice clean chew” were used, though I think most of my guinea pigs didn’t really know what ambergris was, and might have felt differently if they had.

From my point of view, Bompas and Parr had achieved a small miracle. I have always loathed chewing gum, almost to the point of phobia: it took much stiffening of the sinews even to visit the artisanal factory. But I realize now it isn’t the gum that I hate, it’s that hideous, synthetic mint flavor that accompanies it. My mind, and my way of thinking about flavor, has been interestingly tweaked.

*

Bompas and Parr make a good double act. Harry is the boffin, Sam is the showman and charmer, or as he put it, “Harry’s technical and very process-oriented while I do a heap more work with people. That said, we both pitch in on everything.”

I suggested that Bompas and Parr events must be fiendishly difficult to pull off. They have a light, celebratory air about them, but organizing them must be a logistical nightmare. Weren’t there times, dealing with health and safety issues or building regulations when it was hard to keep the lightness?

“On the contrary,” said Sam, “there’s huge fun to be had with health and safety. How often do you get to ask a stranger if they suffer from ear discharge? The trick is to make sure each experience is onion-layered. So if people want to just pop along and have fun that’s cool. But if they want to understand and learn something there’s a weight of thought, deep research and some expert opinions behind the spectacle.”

“A fine example is the Architectural Punchbowl. At face value it was a room flooded with booze that you could float across before drinking. This was fun to do. But if you wanted to know more, you could explore the historical context where British Admiral Edward Russell did a similar thing in 1694, look at the engineering problems or take part in a piece of research put together by psychologists and architects at University College London on dining and perception.”

Clearly Sam wasn’t a man who would admit to difficulty, but even so I thought it must be hard to keep coming up with fresh and interesting ideas that were identifiable as Bompas and Parr territory.

“No way,” said Sam, “we’ve got a sack of ideas we want to crank through and it keeps getting bigger. At the moment it runs to five close-typed pages and we have a pipeline of stuff coming up through into 2012. Harry and I just bother following through on those harebrained ideas everyone has with friends in the pub.”

I don’t think he was being disingenuous. His attitude of “Problem? What problem?” seemed genuine, very refreshing, and dare I say rather un-British. And of course this attitude guarantees an absence of pretension. For all of the science, research and technology that go into a Bompas and Parr project, the guys realize the importance of not being too earnest.

There’s something elemental about what they do. Water, fire and air are usually involved, and on occasion even earth: they made “occult jam” containing sand from the Great Pyramid, and a different jam recipe supposedly contained a fragment of Princess Diana’s hair. There is something louche and decadent about these projects, but also something innocent and good-natured.

As for the future, Sam says, “The big show in December is Taste-O-Rama at the Harley Gallery, in Nottinghamshire, England. We’ll be screening an eat-a-long version of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doomso people can have a movie in their mouths. I’m hyped as we’ve just been sent CAD files of actual monkey brain scans for the chilled monkey brain scene.”

“The thing that’s really special for the screening is the venue. We’ve been allowed into Welbeck Abbey for the first time in history. The place is unbelievable. It has what was once the largest underground room in Europe, a ballroom so large that it would have a separate orchestra at either end when they were having parties in the 1890s. It’s like a forgotten treasure and the event is going to rock.”

You know, I’m absolutely sure it will.